Marco Angrisani, Jeremy Burke, and Arie Kapteyn are economists at the University of Southern California’s Center for Economic and Social Research.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had enormous effects on the U.S. economy. Governmental mandates to temporarily close businesses and schools and individuals remaining home due to fears of infection had stark and immediate impacts on economic activity. There are reasons to be concerned that the first wave of the pandemic may have had serious negative repercussions on many Americans’ financial stability, especially in light of recent empirical evidence documenting households’ limited ability to weather unexpected financial shocks. Limited household savings coupled with the large, negative shock to employment, as well as reduced time available for labor due to increased childcare demands, may have placed considerable strain on many households’ financial situation.

In response to concerns about the pandemic’s possible adverse impacts on households’ financial stability, policymakers passed legislation providing many individuals with Economic Impact Payments (the first round of which was distributed starting in April 2020) and expanded and increased unemployment benefits. This policy response may have meaningfully blunted some of the negative effects of the pandemic on American’s economic security – recent research suggests that the policies may have been effective in offsetting reductions in income and spending.

Americans’ Financial Wellbeing Improved Early in the Pandemic, on Average

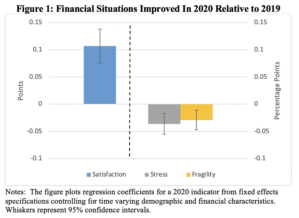

In recent research, we used longitudinal survey data from a nationally representative internet panel to examine the early impacts of the pandemic, and policy responses, on Americans’ financial stability, financial wellbeing, and financial behavior. We find that rather than experiencing large declines, Americans’ financial stability improved, on average, soon after the onset of the pandemic. In particular, we observe increases both in subjective measures, like financial satisfaction, and more objective measures, like financial fragility and savings behavior and balances. For example, as shown in Figure 1, overall satisfaction with one’s financial situation improved by 0.11 points (on the five-point scale) in 2020 relative to 2019. Similarly, the likelihood of experiencing either a “moderate” or “high” amount of stress due to one’s financial situation drops by four percentage points in 2020 from 2019 levels. Financial fragility (i.e. an inability to cover a $400 shock with cash or an equivalent) decreased by approximately three percentage points.

The Stimulus Likely Helped

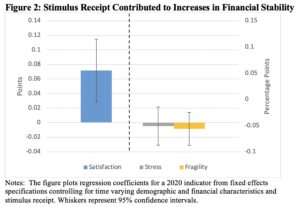

A possible natural explanation for the increase in short-term financial stability, despite huge interruptions to the labor market and a sharp rise in public health risk, is that the relatively robust government stimulus response helped offset some of the pandemic’s adverse effects. We find evidence consistent with this explanation. Figure 2 presents results from the regressions used in Figure 1 after controlling for stimulus receipt. We find that stimulus receipt accounts for nearly all of the reductions in financial stress and financial fragility that we observe in our sample. However, the stimulus is not the whole story, as we found that the stimulus did not explain all of the improvement in financial satisfaction. Even after controlling for stimulus receipt, financial satisfaction was higher in 2020 relative to its pre-pandemic levels. It is possible that the increase in financial satisfaction was partly driven by increased savings activity, also observed early in the pandemic.

Financial Stability Increased Disproportionately for the Economically Vulnerable

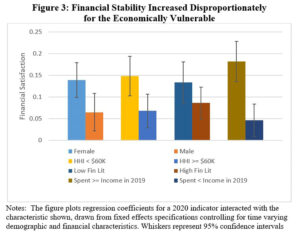

Improvements in people’s average financial wellbeing could still mask important variation in outcomes across sociodemographic groups. For example, consumers who were more economically vulnerable pre-pandemic may have been disproportionately negatively affected by its onset. But our results suggest the opposite was true: financial stability disproportionately improved among respondents who were more economically vulnerable pre-pandemic. Women, those with lower income and financial literacy, and individuals who were spending above their means pre-pandemic all experienced relatively larger improvements in their financial situations, compared to their respective counterparts. For example, Figure 3 shows that individuals spending more than or equal to income in 2019 experienced increases in financial satisfaction that were 0.14 points larger than individuals spending less.

Such improvements appear to be driven, at least in part, by differential impacts of the stimulus payments. We find considerable stronger associations between stimulus receipt and increases in financial stability and saving activity for more economically vulnerable consumers. Our findings suggest that, not only did the government stimulus help prevent widening inequality in financial stability, but it also may have helped close the gap, at least early in the pandemic.

Discussion

Rather than experiencing large reductions in financial stability during the early part of the Covid-19 crisis, Americans’ financial situations improved, particularly for the economically vulnerable. Much of the increase appeared to be attributable to the economic stimulus, which was particularly important for the least financially stable. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that our evidence does not establish causality, and as we only analyze data for early in the pandemic, we cannot evaluate how quickly these financial stability improvements dissipate, nor can we explore the pandemic’s longer-term effects. These questions will be important areas for future research.

Views of our Guest Bloggers are theirs alone, and not of the Pension Research Council, the Wharton School, or the University of Pennsylvania.