John Knowles is a Professor of Economics at Simon Fraser University. Andrew Postlewaite is a Professor of Economics at the University of Pennsylvania.

Why do some people save more than others? One important reason might be that people differ according to their preferences for consumption today versus in the future; another is that their investment returns could differ due to differences in financial acumen. Yet a third is the possibility is that people diverge in their ability or propensity to plan for the future. Each of these theories has been extensively explored in prior economics research.

In practice, however, distinguishing these possibilities using real-world data is difficult or even impossible on the basis of observing households’ income and saving, since the factors that may matter can be unobservable.

Our Work on Future Orientedness

Our recent research has explored “future orientedness,” which we define as the collection of personality traits that contributes to future-oriented behavior, including high savings rates or investment in health and family. Future orientedness encompasses preferences and other personality traits, such as willingness to plan for the future. We do this using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), a nationally representative sample of over 5,000 families followed over time.

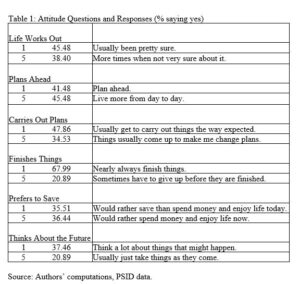

In the early 1970s, PSID respondents were asked questions about their attitudes related to both planning and preferences for saving, and, from 1984 to the present, the PSID went on to ask households about their current wealth. Our analysis focuses on how married couples answered six of the questions, as shown in Table 1. Each spouse responded separately to the attitude questions. Some examples of the attitude questions are: “Would you rather save more for the future or spend your money and enjoy life today?” and “Are you the kind of person that plans his life ahead all the time, or do you live more from day to day?” The questions are generally correlated with each other, but the correlation is relatively weak. For any given question, the responses of each spouse are also weakly correlated. Our interpretation is that the questions/responses reflect persistent personality traits relating to future orientedness.

The Attitude Index

We use the PSID sample of married couples to estimate the effects of the attitude responses on the growth of household net worth many years later, controlling for income and wealth. Next we construct an Attitude Index (AI) for all respondents, based on each individual’s attitude reports and the estimated effects of that attitude.

When we relate each spouse’s AI to the growth rate of household wealth, we find a positive statistically significant relationship. On average, wives’ AI is less important than husbands’ in predicting household saving. Nevertheless, wives’ AI becomes more important as the household AI rises. This may reflect higher future orientedness of such women (marital sorting), or such women’s stronger influence over household decisions (bargaining).

We then simulate a life cycle for married couples from age 20 to 60, and which shows that the measured variation in the attitude index is large enough to play a significant role in the determination of wealth inequality, raising the Gini coefficient for wealth at retirement by 10% or more.

Looking across generations, we also find that parents’ AI are also statistically significant predictors of their children’s completed education and savings as adults.

Interpretations and Implications

Some might worry that reverse causality could be a problem: do attitudes drive wealth accumulation, or does wealth drive attitudes? We argue in the paper that such reverse causality is not a significant concern in our study, since the attitude variables we relate to wealth were measured many decades beforehand. Accordingly, we argue that our baseline Attitude Index measures drive savings success. Moreover, this heterogeneity in future orientation is a powerful driver of wealth inequality.

The fact that the attitude questions predicted financial outcomes so far into the future also suggests that the diversity in attitudes we measure is persistent over time.

The growth rate of wealth is a conventional metric used by macroeconomists to define the national savings rate, and we argue in the paper that our findings have implications for national saving patterns. Most importantly, differences in future orientedness over time or across countries could contribute to differences in national savings rates. Such differences in attitudes toward the future could be driven by cultural variation, though genetic mechanisms have also been proposed. We plan to use PSID data on child development to investigate this issue further.

Conclusions

Our cross-decade research establishes a strong link between reported attitudes about planning for the future and savings, with significant implications for wealth inequality at retirement. We measure the strength of this linkage by constructing an index that predicts the growth rate of wealth associated with variations in the attitude reports, and we interpret this index as a measure of peoples’ future orientedness. Further work on non-pecuniary outcomes shows that this is more than just financial acumen or education. We anticipate that future research can clarify both the nature and the origin of variations in people’s future orientedness.

Views of our Guest Bloggers are theirs alone, and not of the Pension Research Council, the Wharton School, or the University of Pennsylvania.