Moshe A. Milevsky is a Professor of Finance, member of the Graduate Faculty of Mathematics and Statistics at York University, and Fellow of the Fields Institute in Toronto, CANADA. @RetirementQuant on Twitter.

By now it’s well established that there’s a strong and dismal link between a person’s economic prospects and their mortality rates. Stated bluntly, if your income is low, then so is your future longevity. To quote a widely cited US-based study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, “The gap in life expectancy between the richest 1% and poorest 1% of individuals was 14.6 years for men and 10.1 years for women.” And, according to lead author Raj Chetty from Stanford University and his co-authors, this inequality in longevity is getting worse over time.

This, of course, has important implications for retirement planning, and especially the pension and income part of the equation. If you’re not expected to live as long, should you bother saving as much as your likely-to-live-longer neighbour? Can you allow yourself the luxury of spending more during retirement, given your shorter time horizon? More importantly, the growing longevity gap also raises issues of fairness and equity for any retirement system such as social security. Workers with a short life expectancy are implicitly subsidizing those with a higher life expectancy. Should this be tolerated? As the longevity gap gets worse and more people notice it, calls for structural reform will only grow louder.

Problematic Thinking

The problem with this sort of “life expectancy thinking” is that it ignores what economic statisticians and probability theorists call the higher moments of the survival distribution. Thus focusing only on static period life expectancy, which for the US was age 76.4 in 2022, ignores the dispersion – think of the standard deviation of survival, for example – which is something I have written about with Wharton Professor S. Olivia Mitchell.

The issue is that you may expect a shorter lifespan, but the uncertainty associated with that lifespan could be very large. In this case, you might still welcome the idea of being included in a retirement income system along with those facing better longevity prospects. I modeled this in a recent article published in the Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, where I concluded that it would be a serious mistake to shun or opt-out of the annuity “pool,” simply because you might not live as long as the people you are “swimming” with. This is because people with higher anticipated mortality also face greater longevity uncertainty. As a result, you can still benefit from longevity insurance, even if your life expectancy is shorter.

What Must Give?

Nevertheless, those in the highest income groups must be aware that, if this longevity gap trend continues, at some point something must give. So how could we convince them they must sacrifice? Perhaps the answer is to redefine age. Allow me to explain…

Have you ever wondered how old you really are? No, I don’t mean the age on your driver’s license or the date on your birth certificate. That is just the number of times you circled the sun. What I mean is your body’s actual biological age. Yes, think about it for moment.

In parallel with the growing body of research on mortality heterogeneity, there is a medical literature focused on measuring biological age. It’s the same idea as longevity gap, but expressed differently. The length of your telomeres, or the caps at the end of your chromosomes, is one way to measure biological age. Other methods are related to what is called the “epigenetic clock.” Of course all approaches and methodologies need not agree, and if you want to learn your biological age, it will require medical testing.

Yet my key point here is that, sooner or later, people will stop associating their age exclusively with their chronological number. And the better paid will be better able to afford to get tested and monitored, and to link their personal identity with their biological age. This is regardless of how exactly their medical mortality prospects are mapped into a redefined biological age.

How Mortality Maps into Biological Age

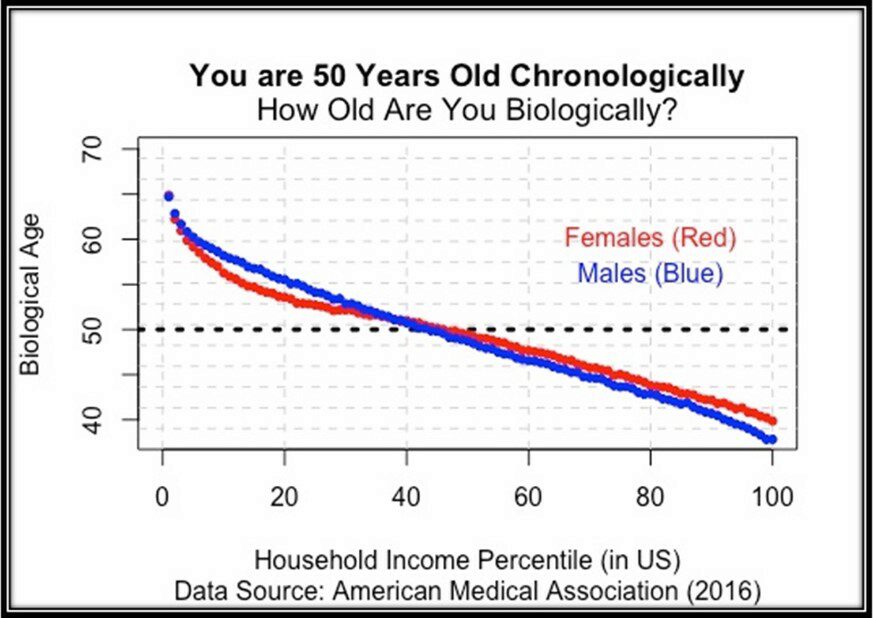

One way this can be done was explained in my 2020 article entitled What is Your Longevity-Risk-Adjusted Age? The actuarial process gets a bit technical, but the figure below shows how mortality rates can be mapped into longevity-risk-adjusted ages. Imagine you are 50 years old chronologically but are in the highest US income percentile. In this case, your risk-adjusted age is closer to 40. By contrast, those in the lowest income group at age 50 chronologically, have a risk-adjusted age of around age 65. This gap of 25 years (65 minus 40) is greater than the above-noted 14 years gap in life expectancy and partially due to the risk-adjustment process. So, we see that the dispersion in risk-adjusted ages is larger than the gap in life expectancy.

Figure Source: M.A. Milevsky (created by author)

OK, What Are the Practical Takeaways?

First, I argue that the conventional approach to thinking about longevity risk has focused exclusively on one dimension, in terms of uncertainty over how long you will live, whereas the newer approach is to think in two dimensions. My study with H. Huang and T. Salisbury explains this point in detail. That is, prudent investors will need to formulate a retirement income plan based on both biological, or risk-adjusted, and chronological ages.

Second, let’s get back to the question of how to persuade higher income people to agree to national pension system reform based on lifetime income differentials. One way would be to set the eligibility age for retirement benefits relative to a suitable risk-adjusted biological age. Yes, everyone should be required to contribute the same and will receive the same benefits, regardless of mortality heterogeneity. That’s egalitarian. But they would only be permitted to claim benefits at a biological (not chronological) age of 65.

Final Thoughts

Look at the above figure again for inspiration. This new approach would imply that people who earned higher incomes would only be allowed to retire at chronological age 75, for example, while the lower income population would be eligible at chronological age 55. Yes, this might appear as a tour de passe-passe, which means ‘sleight of hand’ in French, but perhaps Emmanuel Macron should take notice!

Change the definition of age, not the retirement age.

Views of our Guest Bloggers are theirs alone, and not of the Pension Research Council, the Wharton School, or the University of Pennsylvania.