Peter Conti-Brown

Peter Conti-Brown is an assistant professor at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and Nonresident Fellow in Economics Studies at the Brookings Institution. A financial historian and a legal scholar, he has written widely on financial regulation, banking, and especially central banking, with a focus on the history and policies of the U.S. Federal Reserve. He is the author of the book The Power and Independence of the Federal Reserve (Princeton University Press 2016).

In the summer of 2007, markets roiled as what would become a global financial crisis first started to manifest itself in U.S. capital markets. It was a time when risk models, designed for calmer times, could not capture the sheer magnitude of what lay ahead.

At the time, the Fed’s main interest rate was 5.25%.

After the dust settled on the crisis, interest rates at 5% only showed up in junk bonds and countries with high inflation or histories of default. The Fed’s main rate plummeted to zero. After the Fed’s most recent announcement, it’s now at 1.75%.

For those who depend on higher baseline interest rates, I’ve just told you the good news. The reality is that for five central banks covering much of Europe and part of Asia—the European Central Bank, Denmark, Switzerland, Sweden, and Japan—interest rates have gone even lower, into negative territory.

This brave new world triggers a host of questions, especially for those in the world’s largest economy where interest rates are not negative…yet. Could it happen here? The answer is probably yes. Let’s discuss the mechanics, economics, law, and politics of negative interest rates to understand why.

Mechanics and Economics of Negative Interest Rates

At your next Thanksgiving Dinner, ask your Uncle Chuck or Aunt Sally about negative interest rates. The question is unlikely even to compute, like asking whether we should start reporting football scores in base 12. Why on earth would you give a bank money if it promises to give you back less?

The answer is simpler than you might think. In financial markets and economies with reasonable growth and good opportunities for investable capital, we should never see negative interest rates. Yet many parts of the world are no longer sitting pretty. Aging populations keeping their nest eggs in safe assets, falling fertility, lower inflation, and other factors economists and policymakers are still trying to figure out have created an environment where borrowers have much more power than lenders, in determining the cost of credit. When this occurs, interest rates plummet.

Another way to think of it is by analogy. If you take a year off to go on a road trip, you will need to put your stuff in boxes and your boxes in storage. When you arrive at the storage facility, you will deliver these boxes and pay a fee—it costs money to protect your stuff from the weather, bugs, or thieves. You don’t expect to pay nothing for storage. You certainly don’t expect to get back more boxes of other people’s things from storage.

That’s because the premise of the transaction is that you want your boxes back exactly as you left them. Yet money usually doesn’t work that way: we want not only to protect our money when we put it in the bank, but also to grow it. Nevertheless, when the world becomes more uncertain, and storing money in alternative places means a bigger threat to our nest eggs, then we will quickly change our view about what banks are supposed to do. Rather than offering an investment opportunity, they become storage lockers to keep our money protected from thieves, weather, bugs, etc. When that occurs, of course we will need to pay for that protection, and the payment becomes a negative interest rate.

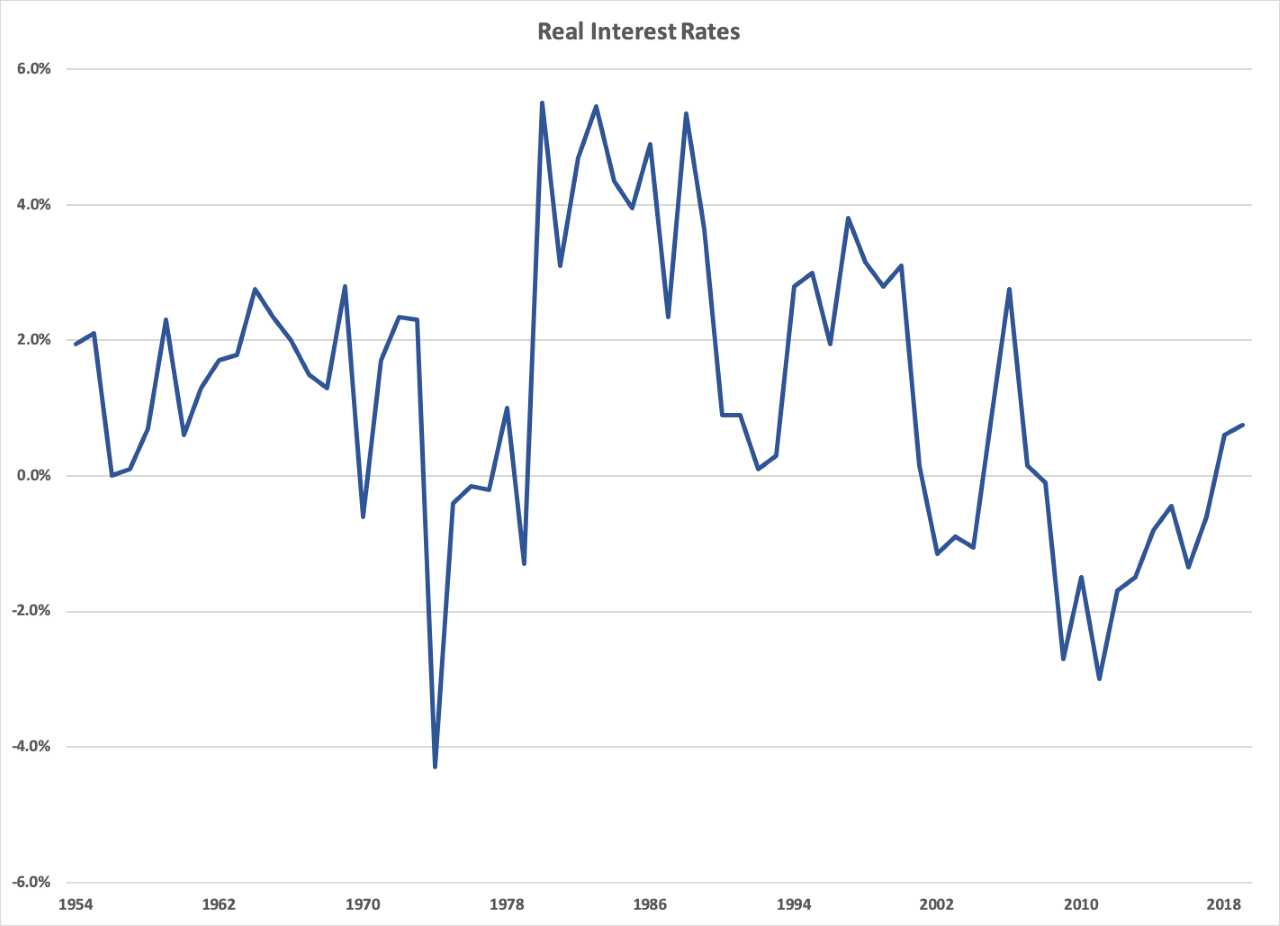

This essay’s titular question—can it happen here?—is misleading in an important sense. It has already happened here, as shown in this chart:

Source: The Federal Reserve System, FRED (subtracting Consumer Price Index from Federal Funds Rate).

This is the chart of U.S. real negative interest rates, or the target interest rate minus inflation. When the interest rate falls below inflation—as happened in the 1970s and 1980s, for example, and more often than not in the 21st century—we are in a world of negative interest rates.

Law of Negative Interest Rates

Even so, a central bank crosses a Rubicon when it announces not only that its target rate is less than inflation, but that its target rate is actually below zero. It is not at all clear that the U.S. Federal Reserve can undertake that bigger experiment, even if the economy required it, in part due to the law. The Federal Reserve Act has a number of restrictions on, for example, the kinds of assets the Fed can buy on the open market, restrictions not in place for other central banks. This has already influenced the shape of U.S. monetary policy, as former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke has discussed.

U.S. law on negative interest rates is murkier in other areas: for instance, there is no legal prohibition on targeting negative interest rates. The most relevant statutory provision states merely that the Fed shall run its monetary policy “so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates,” the Fed’s so-called monetary policy mandate. Temporary negative interest rates are consistent with this mandate, in theory.

The problem comes in looking for the authority for the Fed to charge banks for the reserves they hold at the Fed. There’s no clear authority for this, for the purpose of negative interest rates; there’s also no clear authority preventing it. Therefore the Fed would be taking a legal gamble if it went down this path. It seems clear that Congress didn’t have negative interest rates in mind when it passed the Federal Reserve Act, so the question the Fed’s central bankers would have to answer is whether they are willing to take the risk anyway.

Politics of Negative Interest Rates

The risk, of course, is a political one. The political constituency for negative interest rates in the U.S. appeared, until recently at least, to be the same as that for the buying and selling of babies. With so little popular enthusiasm for the proposal, it is little wonder that Fed Chair after Fed Chair—from Bernanke to Yellen to Powell—have denied any intent in following Europe and Japan into negative territory.

In our upside down political world, though, there may be an opening. In September, President Trump continued his assault on the Fed, but now offering a new critique:

The Federal Reserve should get our interest rates down to ZERO, or less, and we should then start to refinance our debt. INTEREST COST COULD BE BROUGHT WAY DOWN, while at the same time substantially lengthening the term. We have the great currency, power, and balance sheet. The USA should always be paying the the [sic] lowest rate. No Inflation! It is only the naïveté of Jay Powell and the Federal Reserve that doesn’t allow us to do what other countries are already doing. A once in a lifetime opportunity that we are missing because of “Boneheads.”

Those two little words in the first line —“or less”— may imply a sea change in Federal Reserve policy. If a significant chunk of the electorate follows the President’s enthusiasm for negative interest rates, we may see here, as in so many other areas of our public policy, new constituencies forming around new ideas and new experiments. Sometimes for better, sometimes for worse.

Views of our Guest Bloggers are theirs alone, and not of the Pension Research Council, the Wharton School, or the University of Pennsylvania.