Linda-Eling Lee is global head of ESG and Climate Research at MSCI and a member of the firm’s Executive Committee.

From Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to the perils of a warming planet, investors increasingly turn to environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors for answers about how their investments intersect with a host of complex and evolving issues in society.

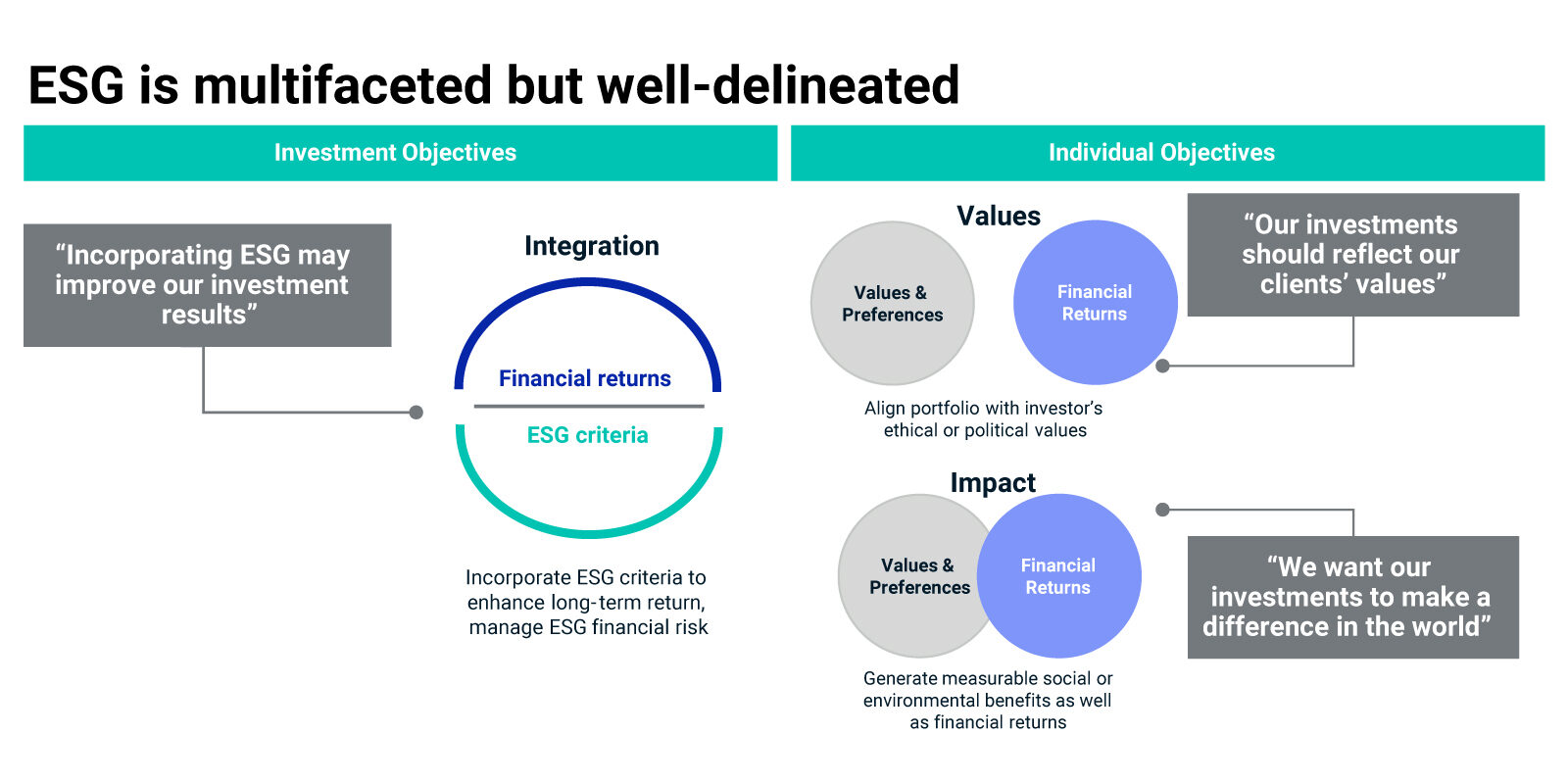

Yet despite the breadth of the term, ESG cannot be consolidated into a catchall. Though often invoked as a label for sustainability, ESG strategies have come to entail a multitude of facets and a high degree of precision thanks to decades of improvements in data and analytics that allow such measures to reflect the variety of investors’ conceptions and goals. By articulating a desired outcome and using as specific an input as possible to target it, retirement plan sponsors can harness ESG in pursuit of their aims.

ESG’s dual legacy

ESG investing comes primarily from two sources: a vision to align portfolios with social objectives investors care about and a desire by investors to identify financially relevant risks not captured by the conventional measures of the past. The ESG data and ratings that exist in the market today reflect this dual legacy.

With regard to the financial motivation, the available evidence suggests that ESG ratings designed to measure industry-specific sets of ESG issues do illuminate companies’ long-term risk and performance. For example, while not indicative of future results, the top fifth of companies by industry-adjusted ESG ratings showed higher profitability and lower levels of stock-specific risk than the bottom fifth of such companies in a forthcoming analysis by MSCI ESG Research that examined companies in the MSCI ACWI Investable Market Index (IMI) over a period of 15 years ending in December 2021.

While the use of ratings to identify financially relevant ESG risks has become a dominant force in driving adoption of such investing by mainstream financial firms, the values approach still applies for many investors and their investment strategies. In fact, issues ranging from concerns with human rights in specific regions to a desire to promote positive impact on one or more of the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals are motivating some investors to incorporate ESG measures into their investment process to ensure alignment with their professed social values.

Implementing ESG strategies

The growing availability of data is improving capture of the multi-dimensionality of ESG concepts along with the topics covered by ESG data, which today ranges far beyond information disclosed by companies. The many often-unstructured datasets in the public domain, together with advances in artificial intelligence and modeling, now allow investors to deepen insight into such risks as the proximity of a company’s operations to sensitive cultural sites, or to extreme weather — risks that companies themselves may lack knowledge of on their own.

Though approaches for integrating ESG vary, several guidelines can help investors implement such strategies.

- Know what you aim to measure. An investor who aims for a specific outcome, such as greater carbon efficiency, may wish to specifically measure companies’ carbon efficiency rather than other broadly related criteria. The MSCI ACWI ESG Focus Index and the MSCI ACWI ESG Leaders Index, for example, reported carbon intensity of roughly 31% and 36% versus the MSCI ACWI Index, respectively, as of Jan. 31, 2021. Yet because carbon emissions are not used as a direct input into the methodology for constructing those indexes, their carbon intensity is an unintended byproduct of the construction methodology that could conceivably differ in other time periods. By contrast, the MSCI ACWI Low Carbon Target Index and the MSCI Climate Paris Aligned Index, which aim to minimize their carbon intensity by design, reported carbon intensity levels roughly 70% and 80% lower than the MSCI ACWI Index, respectively, as of Jan. 31, 2021. Plan sponsors with a clear idea of the objective they seek — whether that is to eliminate exposure to certain types of weapons or avoidance of labor-rights violations, or a desire to exceed certain thresholds for board diversity — might benefit from a more precise match between their desired outcome and the specific ESG measures used in the investment process.

- Imposing a limited number of values-based exclusions. When values-based exclusions are kept to a minimum, tracking error — a measure of how well a fund tracks its benchmark during the investment period — of certain ESG indexes can be low. For example, a model portfolio designed to track a benchmark such as the MSCI ACWI ESG Screened Index, which excludes companies that produce tobacco or designated controversial weapons, violate U.N. Global Compact principles, or earn revenue from the sale of thermal coal or oil sands, incurred a relatively low tracking error of 0.47% over nearly nine years that ended in February 2021 despite the exclusion of 158 stocks from the index of nearly 3,000 companies during that period. Nevertheless, a limited number of exclusions means precisely that: Approaches with minimal exclusions and low tracking error could allow inclusion of many firms facing social and environmental controversies; plan sponsors may wish to be aware of these trade-offs.

- Investment strategies that overweight better ESG performers within industries can trigger unintended exposure to factors that may impact risk and return. Research by MSCI has found mild positive correlations between ESG ratings and exposure to such factors as low volatility, larger size and higher financial quality that may explain the performance of stocks. An analysis of select ESG indexes in the volatility that accompanied the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic shows that indexes with stronger ESG profiles tended to have higher exposure to the low-volatility factor. This exposure shielded their constituents during sharp sell-offs, but it also dampened returns during market rallies.

- Fund managers have a choice between bottom-up and top-down approaches for integrating ESG across their equity portfolios. A bottom-up implementation addresses portfolios one by one. While this approach can accommodate minimal disruption to actively managed portfolios, it also can lead to inconsistencies in ESG standards across portfolios and generate suboptimal outcomes. A top-down implementation starts with the adoption of an ESG benchmark to measure performance of both indexed and active mandates. That can offer a more comprehensive approach, but it may require more significant changes to existing allocations.

Whether plan sponsors aim to minimize exposure to particular countries, align with their participants’ professed climate goals, or ensure that investments accord with their expressed social values, it is important to be specific. Clear and consistent ESG measure can then be tied to those specific aims and contribute to investors’ better understanding how ESG links to long-term financial performance.

Views of our Guest Bloggers are theirs alone, and not of the Pension Research Council, the Wharton School, or the University of Pennsylvania.