Patricia Boyle is a neuropsychologist at Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center. Olivia S. Mitchell directs the Pension Research Council at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. Gary R. Mottola is the research director at the FINRA Investor Education Foundation. Lei Yu is a statistician at Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

Financial and health literacy are crucial for older people. If older adults lack an understanding of basic financial and health concepts, along with the ability to apply skills such as budgeting and saving, it becomes increasingly difficult for them to do a good job managing money and making informed choices about medical care, insurance, and day-to-day health management.

Our recent research study investigated whether and how financial and health literacy changes with age by tracking more than 1,000 older adults annually and asking them questions about financial and health knowledge for up to 12 years. Participants were older adults living in the community who agreed to participate in the Rush Memory and Aging Project; they averaged 81 years old at the start of the study. This research is unusual in being able to follow the same people over time, whereas prior studies have mainly focused on people of different ages interviewed at a single point in time.

Participants were asked to answer 23 questions, eight of which assessed numeracy (e.g., performing basic calculations or converting between numbers and percentages). The remaining 15 questions tested knowledge of financial terms, institutions, and investments. The assessment also included nine items that measured knowledge of health information and concepts designed to measure health literacy. All questions had multiple choice or true/false answers.

What we learned

A large majority, around 87% of study participants, experienced a decline in their financial and health literacy scores with age. At baseline, the average combined correct score across all participants was about 70%. Notably, this average then declined by about 1 percentage point per year. In other words, someone who earned a score of 70% at baseline would have only been able to answer 60% of the questions correctly a decade later. Moreover, those who scored the lowest at baseline were also most likely to experience declines, as were older and less educated respondents.

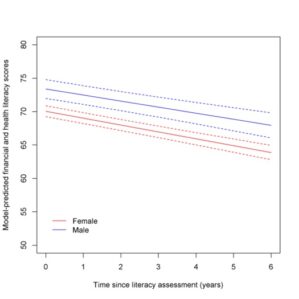

We also documented that, on average, men scored about 3.6 percentage points higher than women at baseline, even after controlling for age, income, education, and medical conditions. Interestingly, the rate and likelihood of decline did not differ significantly by gender; financial and health literacy deteriorated for both men and women in parallel (see Figure 1). And perhaps surprisingly, no demographic factor other than age was related to the rate of decrease.

Figure 1. Rates of decline in financial and health literacy for older males and females.

Note: The figure illustrates declining financial and health literacy for older males and females estimated from a linear mixed effects model. The blue solid line represents the mean rate of decline in financial and health literacy for a representative male participant with average age and education, and the two dash lines represent the 95% confidence band. The red solid line represents the mean rate of decline in literacy for a representative female participant with average age and education, and the two dash lines. Source: Boyle, Mitchell, Mottola, and Yu (2025).

Wider implications of our study

Lower financial and health literacy can lead people to make numerous money management mistakes, lose money to scams and fraud, and fail to navigate complex medical decisions. With less time to recover, such losses can be particularly dangerous for older individuals.

With this in mind, we posit that it is essential to help older adults maintain and even enhance their financial literacy when possible. Knowing how the decline in financial and health literacy affects older adults could therefore be helpful when tailoring messages and programs to help prevent some of these negative outcomes.

For those involved in efforts to improve older adults’ financial well-being, the finding that women have lower levels of financial and health literacy, and that this gap does not close with age, is noteworthy. Due to older women’s longer average lifetimes, their lower financial and health literacy, and greater potential to be living alone for many years at the end of their lives, they may be especially vulnerable to financial and health shocks as they age. They are therefore likely to benefit from initiatives aimed at maintaining and building financial literacy at older ages, along with efforts to develop and promote such programs.

Although the gap between men and women persists as they age, the similar decline trajectories suggest that early interventions—well before older age—could help boost baseline literacy for everyone, even if other approaches are needed to close the gap.

Views of our Guest Bloggers are theirs alone, and not of the Pension Research Council, the Wharton School, or the University of Pennsylvania.