By: Gene Kalwarski

Gene Kalwarski is CEO and founder of Cheiron Inc., and actuary to many of the nation’s largest multiemployer and public pension plans.

Some observers have recently suggested that multiemployer or industry pension plans in the U.S. have bounced back fully since the 2008 recession, and it’s time to break out the champagne. Not so fast!

For years, the gold standard for determining the financial stability of pension plans was their funding ratio, or the ratio of assets to liabilities. Conventional wisdom held that pension plans with assets sufficient to cover 80 percent or more of their liabilities were reasonably well-funded. But a pension plan’s funding ratio is just a snapshot at a point in time. Focusing only on the funding ratio tends to lull plan sponsors into believing they are financially stable even when they are not.

A Better Solvency Measure

A more meaningful way to determine which pension plans will survive in the long term is to examine not only their funding ratios but also their maturity. For example, industry pension plans are generally termed “mature” if they have more retirees than active workers and a negative net cash flow, paying out more in benefits than they’re receiving in contributions.

A key takeaway from the financial crisis of nearly a decade ago is that even the apparently best-funded pension plans are vulnerable to downturns if they are mature. In fact, it is possible that a plan 50 percent funded but not mature could be better positioned to withstand a recession than a mature plan considered “safe” with a funding ratio of 80 percent or higher.

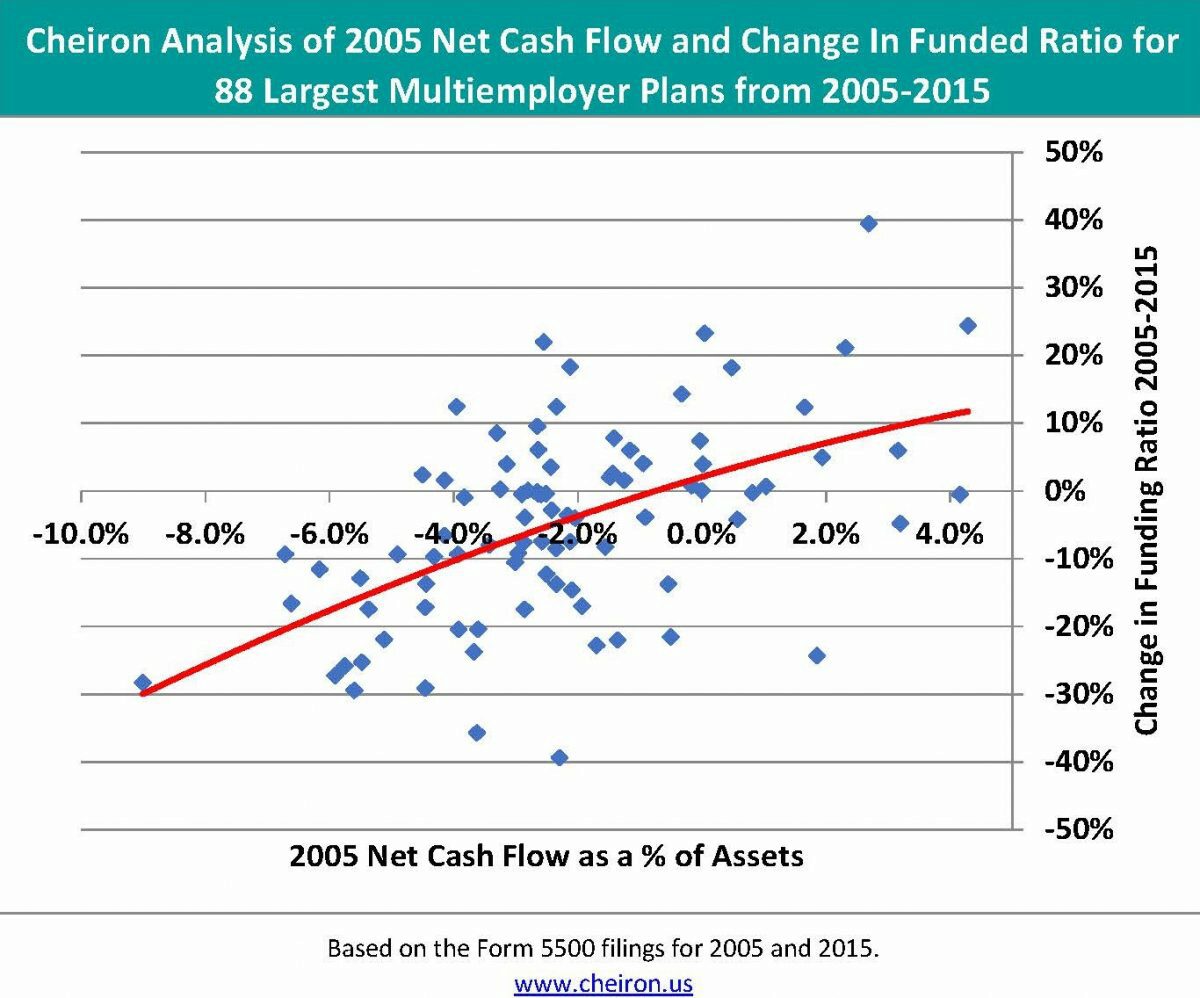

To examine how multiemployer pension plans withstood the downturn, we have analyzed 88 of the largest multiemployer plans for which data are publicly available going back to 2005, before the Great Recession. We then compared these results with 2015 data. The set of plans we evaluate include 69 percent of all participants in multiemployer plans, and they hold assets totaling 59 percent of all such pension assets. Our analysis showed a very close link between a plan’s net cash flow before the economic downturn and the change in its funding levels since then. In particular, the worse a plan’s cash flow position in 2005, the greater its funding ratio fell between 2005 and 2015. This is depicted in the chart below.

Moving Toward a Solution

In our view, pension plans that are well-funded but mature must act now, before the next downturn hits. They should review their asset allocation and consider whether to dial back on their risk. Our analysis reveals that, by the time the plans have more than 2.5 retirees per every active worker and a negative cash flow of more than 5 percent of assets, it may be difficult for them to recover from another downturn. One approach would be for mature pension plans to use interest and principal payments from their bond portfolios to pay benefits, instead of actively trading bonds and exposing their plans to interest rate risk.

Legislation recently proposed by Ohio Democrat Sen. Sherrod Brown to rescue financially-troubled union pension plans goes one step further than this. His proposal is that a new government entity within the US Treasury be designated to lend money to “critical and declining” pension plans, so long as the money is used to pay off benefits and is not invested in the stock market.

This proposed legislation requires pension plans to use the loans to purchase annuities, or to cash match and thus immunize all benefits owed to retirees. In other words, pension plans would be required to mimic what insurance companies do when they annuitize: invest in bonds, not equities. Early analysis suggests that this legislation could save even the most poorly funded plans.

This piece was originally posted on December 6, 2017, on the Pension Research Council’s curated Forbes blog. To view the original posting, click here.

Views of our Guest Bloggers are theirs alone, and not of the Pension Research Council, the Wharton School, or the University of Pennsylvania.