Nora Super is the senior director of the Milken Institute Center for the Future of Aging and executive director of the Alliance to Improve Dementia Care; she served as the executive director of the White House Conference on Aging during the Obama administration. Jason Davis is a senior associate on the Innovative Finance team at the Milken Institute; he holds a BFA from Syracuse University and an MBA from Loyola Marymount University. Caroline Servat is an associate director at the Milken Institute Center for the Future of Aging; she holds a BA from Bates College and a Masters of Public Policy from the University of Southern California.

Long-term care (LTC) in the United States has suffered from underfunding and inattention for decades. Failure to address this crisis has enabled widespread coronavirus infection and death in our nation’s nursing homes and assisted living facilities. Nursing home residents and their workers make up about 42 percent of all COVID-related deaths (KFF). Horrifying and inexcusable? Yes. Unexpected? Tragically, no.

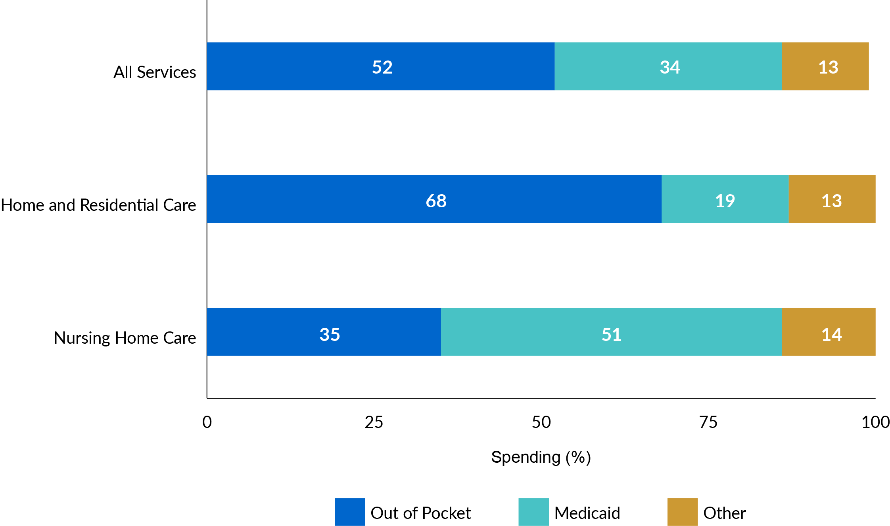

By 2030, one in five US residents will be age 65+, and 70 percent of them are expected to need LTC at some point in their lives. The declining availability of family caregivers and limited financial resources will make adequate care even harder to find. And the costs of LTC are staggering. According to Genworth, a nursing home’s price averaged about $102,200 per year in 2019, or well-over twice an older (65 and up) middle-income family’s income. Individuals and families bear most of these costs, paying 52 percent of LTC costs out-of-pocket, including 68 percent on home and residential care and 35 percent of nursing home care (Figure 1). Medicaid finances most of the remainder for low-income people. Private LTC insurance (LTCI) pays less than 3 percent.

Figure 1: Average Lifetime LTC Spending for Adults Aged 65+ by Source

Note: From Favreault, M. M., & Dey, J. 2015. Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Americans: Risks and Financing Research Brief. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/long-term-services-and-supports-older-americans-risks-and-financing-research-brief.

Drawing on extensive market research, the Milken Institute recently analyzed the most significant barriers to meeting the LTC needs of Americans. It also identified three of the most promising areas for increased financing and delivery opportunities: public and private LTCI solutions, Medicare expansion solutions, and technology solutions.

Public and Private Long-Term Care Insurance

Enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, the Community Living Assistance Services and Supports (CLASS) Act provided a voluntary, publicly administered LTCI program. In 2013, the Obama administration repealed CLASS after concluding that it was financially unsustainable. Since then, the number of private insurers offering LTCI has plummeted from slightly more than 100 in 2004 to about a dozen today, and consumer uptake has declined dramatically. While some of this is due to consolidation, the more significant force driving the exit is a lack of profitability.

This market failure stemmed from flawed actuarial assumptions made on early policies, resulting in significant premium increases. Insurers now face consumer mistrust and a misperception that Medicare will cover LTC expenses. For those who want to buy LTCI, most LTCI premiums are beyond middle-class households’ financial reach.

Despite these challenges, efforts to reinvigorate the private LTCI market are underway. Recently, hybrid products have increased in popularity, combining LTC benefits with life insurance or annuity products. Consumers find these policies more attractive because they can protect against significant premium increases, but they can still be prohibitively expensive, and may not expand the market to middle-class Americans. Continued product design experimentation is necessary to find the right balance of affordability and level of coverage. Policymakers are also exploring new ways to help individuals pay for LTCI premiums through tax-advantaged savings vehicles and other incentives.

Several states have stepped up efforts to address the LTC financing deficit. Washington State embarked on a first-in-the-nation public LTCI program that provides a maximum benefit of $36,500 ($100 per day), indexed to inflation, for qualifying residents who have contributed to the program via payroll taxes. This front-ended approach allows benefits to kick in after only a short waiting period. Others have advocated for a “catastrophic” model with a longer waiting period (e.g., two years), but no lifetime claims limit, which would complement existing private LTCI plans better. Still, the front-ended strategies help finance out-of-pocket expenses for those not eligible for Medicaid, and it is hoped, keep them off Medicaid rolls. Absent a federal LTCI program, state-level experimentation will be imperative as the demand for long-term services and supports (LTSS) increases.

Medicare Expansion

Historically, the US Medicare program has paid only for acute care services. Specifically, Medicare does not provide coverage for nursing homes or personal care needs, such as bathing or dressing. Despite this reality, any Americans mistakenly believe that Medicare pays for these services.

With growing evidence confirming that home- and community-based services (HCBS) save costs in the long run, Medicare has begun experimenting with covering non-medical services, such as transportation and home-meal delivery. Through enacting legislation in 2019, private Medicare Advantage (MA) plans can now pay for services that are not primarily health-related. These “special supplemental benefits” can target the needs of chronically ill enrollees.

MA plans cautiously rolled out these new benefits in 2020, and experts anticipate a broader distribution of benefits across markets in the future. Medicare is likely to continue to test and expand the delivery of HCBS under the Value-Based Insurance Design model now permitted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in all 50 states. Other ideas worth exploring could establish a cash benefit for Medicare beneficiaries to use for LTC expenses or create new Medigap options that cover non-medical benefits.

Technological Developments

Technology has substantial potential to fill a wide gap between the demand for and availability of LTSS, given our rapidly aging population and high costs for care. Perhaps one of the few silver linings of the COVID-19 pandemic, the public health crisis has rapidly accelerated telehealth access and highlighted the need for more cost-effective, high-quality integrated care programs for older adults living at home and in residential care settings.

In March 2020, CMS responded to COVID-19 by expanding access to telehealth services for Medicare beneficiaries. In recognition of the need to limit the virus’ community spread, the adoption of telehealth services expanded rapidly. From March to April 2020 alone, Medicare beneficiaries increased their telehealth use by nearly 120-fold, from 11,000 to 1.3 million.

Several public/private strategies are worth exploring to advance technology solutions that would enhance LTC financing and delivery. Funding to support pilot testing of technology effective in the health care sector could evaluate predictive analytics, telehealth, remote monitoring, and assisted mobility across different care settings. It would also be useful to focus on the funding gap for the development and adoption of technology supportive of LTC. For instance, a federal-level collaboration with small businesses could benefit from seed fund that target aging-related technology companies. Alternatively, an impact investment fund could support the development of emerging technologies. In addition, public/private programs helping insurers and care providers offer the technology at low or no cost to users would be useful.

The Outlook

For too long, we have turned a blind eye to the challenges facing older adults and people with disabilities in need of LTC. These challenges will only worsen, unless the market gaps and failures inherent in LTC financing and delivery are addressed. Since governments alone are unlikely to solve this problem alone, public and private partnerships offer new paths to reverse the course of this crisis.

Views of our Guest Bloggers are theirs alone, and not of the Pension Research Council, the Wharton School, or the University of Pennsylvania.