Michaela Pagel is an Associate Professor at the Olin Business School of the Washington University in St. Louis. Arna Olafsson is an Associate Professor at the Copenhagen Business School.

Defined benefit pensions are becoming less common in many developed countries, while the rise of defined contribution plans is shifting the responsibility of preparing for retirement onto individuals. This makes it increasingly important for people to understand the need to save more and hold less debt. Yet many people have little savings and hold too much debt by the time they retire. Our new research studies retirees to examine the question of whether people plan properly and save enough for retirement.

Analytic Approach

We use anonymized transaction-level data provided to us from a personal financial management software firm in Iceland to investigate how people’s liquid savings and consumer debt change in the 10-year window around retirement. After they retire, the individuals we track are 4% more likely to have liquid savings and save 28% more. Additionally, they are 4% less likely to overdraw their checking accounts post-retirement, compared to beforehand. New retirees also reduce their overdraft debt by 55%, which is interesting since, in Iceland, overdrafts are a common way to roll over high-interest unsecured consumer debt.

When people anticipate that their income will fall at retirement, they should rationally save more anticipating this decline, rather than afterwards. And in Iceland, people do face a sizable income drop when they retire. Yet this should not come as a surprise, since people can easily look up how they will receive in pension benefits, which are indexed to the consumer price level. But what we find is that people’s spending drops by more than their income falls at retirement. This is why we see rising savings and a decrease in their consumer debt.

Potential Explanations for this Puzzle

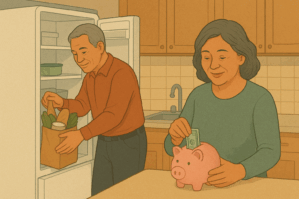

One possible reason for this pattern could be that people have fewer work-related expenses after retirement. For instance, they could undertake more home production, such as substituting home-cooked meals for eating out, or do their own repairs instead of hiring a fix-it person.

Yet if people knew in advance that they could save more by retiring, it stands to reason that they should retire as early as possible – unless the pension they would receive by working longer exceeds the additional money they would save by retiring. In Iceland, however, this not the case. After age 67, the additional benefits in pension payments from working for one more month are small: approximately 0.5 percent or US$10/month in additional pension income. These increases in pension income are much smaller than the average savings from retiring for our sample, which equal monthly reductions in overdrafts of approximately US$102 and monthly increases in liquid savings balances of approximately US$210. Therefore, individuals should retire as early as possible as they can save more by doing so. Nevertheless, we find that individuals continue to work for many months and sometimes years beyond reaching the retirement eligibility age. For this reason, the puzzle cannot be fully explained by falling work-related expenses.

Alternatively, it might be that health shocks and increased medical expense risk could lead people to simultaneously retire and boost their need for precautionary savings. Yet we believe that this is unlikely since Iceland is a Nordic welfare state, so the pension is reliable and predictable, the national health care system is comprehensive, and retirees will not face large medical expense risks (unlike in the US). Another reason is that people do not increase their spending on medications after retirement. And finally, if individuals rationally expected an increase in medical expenses after retirement, then they should have saved more before retirement rather than only afterwards. Yet this is not what we see.

We also evaluate several other potential explanations, such as that declines in consumer debt could be due to decreases in retirees’ borrowing capacity. But the data do not reveal declines in borrowing capacity or decreases in liquidity around retirement. Our study also discusses whether other factors could play a role, including labor-leisure substitution, intra-household bargaining, consumption insurance, lump-sum pension payments, and inventory savings. In sum, these alternative rationales cannot explain our findings.

Resolving the Puzzle

In order to solve the twin puzzle of why consumption falls at retirement, and why people continue to work even though they could save by retiring, we argue that during their working lives, people struggle to keep their spending under control as well as save for emergencies and retirement on top of many other stressors, and in particular, work stresses. After retirement, people have more time to plan and so can be more successful managing their finances, cutting spending and boosting savings.

Views of our Guest Bloggers are theirs alone, and not of the Pension Research Council, the Wharton School, or the University of Pennsylvania.