Vicki L. Bogan is a professor of Economics in the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University and a Research Associate with the National Bureau of Economic Research.

The definition of the term ‘financial inclusion’ has changed over time. Originally, it meant that people had access to formal banking institutions. Today, the term is broader, including not only having access to banking institutions, but also access to useful and affordable financial products and services. This expanded definition of financial inclusion now encompasses the entire financial network including savings, payments, investments, credit, and insurance. Unfortunately, the financial network is far from inclusive in the U.S. For instance, more than 24 million households were recently deemed to be either unbanked or underbanked, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

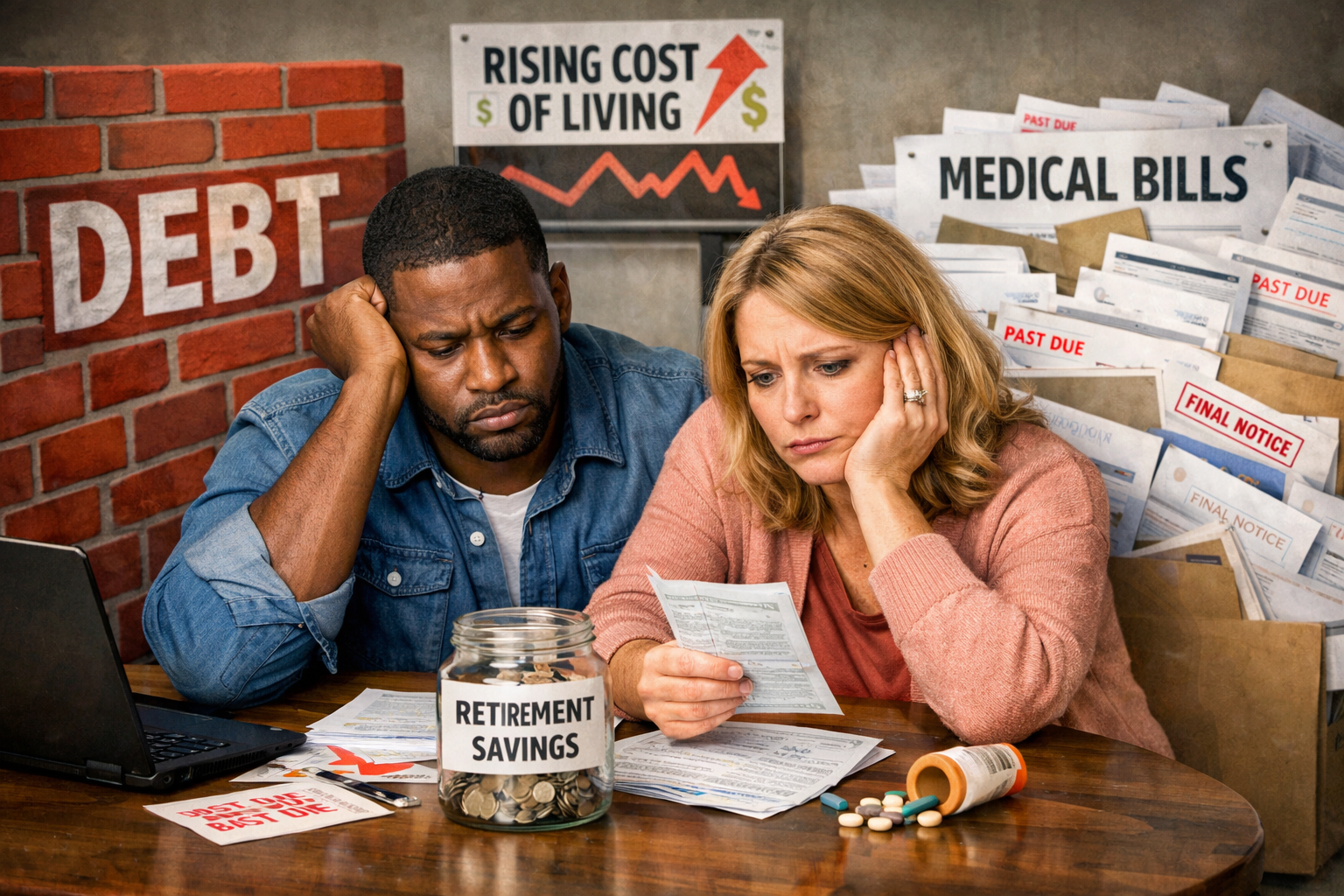

My recent chapter in the Pension Research Council’s new book on Reducing Retirement Inequality analyzes several key obstacles to retirement savings that perpetuate inequality. In what follows, I take up each in turn.

Barriers to Retirement Savings

The US Social Security program was intended to provide American households with a basic level of financial security, yet social security benefits have been insufficient to eliminate poverty for older women. Furthermore, retired African American women have the highest rates of poverty due to their low lifetime earnings and correspondingly low social security benefit levels. Older Latinos are also less likely to benefit from social security, as many workers have informal employment arrangements. Moreover, some who came to the US later in life are ineligible for benefits because of insufficient payroll tax contributions.

Employer-sponsored retirement plans of either the defined benefit or defined contribution variety are also important retirement savings vehicles in the US. Defined benefit plans promise guaranteed benefits on retirement. Defined contribution plans enable employee contributions through payroll deductions, are tax-advantaged, and are usually supplemented by employer matching funds. Yet not all jobs offer these plans. For example, one-quarter of civilian workers in the US lack access to an employer-sponsored retirement plan, a differential access that exacerbates retirement savings inequality. This is particularly concerning since retirement account participation is the lowest for workers in lower-paid jobs.

Another factor to highlight is that holding stock is an important means for wealth accumulation, yet many fail to save via stock holdings. Transaction and information costs have been offered as the most likely explanations for these low financial market participation rates, especially in underrepresented minority communities. This implies that assets such as stocks and mutual funds are less commonly used as sources of retirement income for minority and low-income households.

A final factor accounting for retirement wealth inequality is limited use of financial advisors and planners, which is a factor more strongly associated with retirement planning than is employer-provided financial education. However, access to professional financial advice varies geographically: 13 states have been classified as Financial Advice Deserts (Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Idaho, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, West Virginia, and Wyoming). This geographic variation has been shown to explain not having a retirement account and not contributing consistently to the account.

What Can Be Done?

Given the magnitude and scope of financial exclusion, it is not surprising that many Americans feel underprepared for retirement. To address the shortfalls, researchers, policymakers, financial institutions, and employers will need to work in partnership. Some propose that the Retirement Savings for Americans Act providing all with access to a retirement plan is the solution for low- and middle-income households. Nevertheless, a more comprehensive approach to increase financial inclusion throughout the entire financial network would also help facilitate retirement preparedness.

Specific examples could include extending financial planning to lower-income adults, along with facilitating more access to financial advice. Additionally, restoring solvency to social security will be essential to ensure that benefits are paid to those participating in the program. Credit unions, fintech firms, and community banks could do more to reach out to the unbanked. And offering more access to financial education in the schools has potential to help the next generation of retirement savers.

Views of our Guest Bloggers are theirs alone, and not of the Pension Research Council, the Wharton School, or the University of Pennsylvania.