Anton Braun is a Professor of economics at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies in Tokyo Japan (GRIPS) and an International Senior Fellow at the Canon Institute for Global Studies (CIGS). Karen Kopecky is an economic and policy advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland and an Adjunct Professor at Emory University.

America is aging and the risk of needing costly long-term care (LTC) late in life is significant. One in three Americans will face a nursing home stay longer than 100 days and the median monthly cost for a shared room in 2024 was over $9,000. Medicare, the primary payer of acute care for retirees, does not cover LTC expenses. Instead, Medicaid provides a base level of coverage to individuals having less than $2,000 in countable assets and low retirement income. Despite limited public insurance, the US private long-term care insurance market is small, insuring only about 10 percent of aggregate long-term care expenditures, and individuals pay for over half of long-term care expenses out of pocket.

Why do so few buy private LTC insurance?

While there are several factors at play—policies are costly to produce and administer, and underwriting is stringent—a crucial piece of the puzzle is Medicaid’s design, which substantially reduces peoples’ willingness to pay for private insurance. Medicaid is a government-run, means-tested program, and many elderly run down their assets to qualify, instead of purchasing private LTC insurance. Medicaid is also a secondary payer: it only pays benefits once private LTC insurance has been exhausted. Our new study finds that Medicaid’s crowding-out effect on private insurance is primarily due to its secondary payer status.

Why the “secondary payer” rule matters

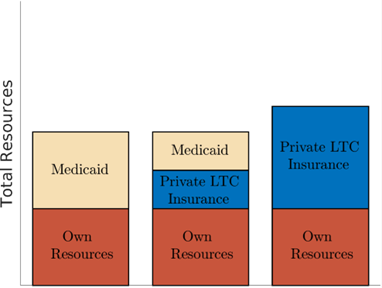

Figure 1 illustrates Medicaid’s secondary payer provision in action. Suppose you require LTC in a nursing home and you meet Medicaid’s means-test. If you have no private insurance (left bar), Medicaid covers your nursing home costs. Now suppose you own a private LTC policy (middle bar): Medicaid reduces its payment dollar-for-dollar while your private policy pays instead. Your total resources available for care don’t rise—you simply replace a free public benefit with a costly private one. You can increase your level of resources in the nursing home state if you purchase enough private insurance and forgo Medicaid benefits (right bar), but you end up paying for a lot of care that Medicaid would have provided for free. That’s a tough sell.

Figure 1. Total Resources when Medicaid is a Secondary Payer

Source: Braun and Kopecky (2025).

Two reform paths—and one clear winner

In our research, we consider two ways to make private LTC insurance more attractive:

- Expand LTC Partnership Programs. These allow people who buy qualifying private LTC policies to protect an equivalent amount of assets from Medicaid’s means test. In principle, this encourages middle-class households to insure. In practice, complicated rules hold back participation: minimum benefit requirements, inflation riders that raise premiums, premium increases after years of paying in, and state-specific restrictions (including home equity limits) that can still bar access to Medicaid once private benefits run out. Moreover, not all states participate, and rules vary.

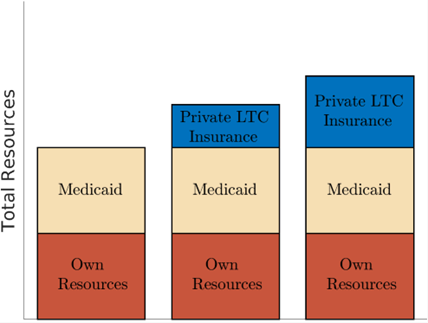

- Make Medicaid the primary payer for long-term care. This reform would keep Medicaid’s means tests in place but change the order of payment so that Medicaid pays first. Figure 2 illustrates why this change increases the size of the private LTC insurance market. Households can “top up” public coverage with private LTC insurance, allowing them to purchase more amenities during nursing home stays, cover gaps, and protect more resources for the future. Private policies would then become a true complement to, rather than a substitute for, public coverage.

Figure 2. Total Resources when Medicaid is a Primary Payer

Source: Braun and Kopecky (2025).

We find that making Medicaid a primary payer increases private LTC insurance take-up rates from below 10% to over 60%. Moreover, the size of aggregate Medicaid expenditures doesn’t change much because Medicaid benefits are still means-tested. This straightforward change to Medicaid’s design leads to widespread improvements in wellbeing.

Who benefits—and what happens to Medicaid outlays?

Under this reform, middle-class households would gain the most. They buy private coverage to supplement Medicaid, ending up with better protection against nursing home risk. Yet low-income and affluent households would also come out ahead. Current public insurance benefits are maintained for those with low levels of resources, while total Medicaid spending falls under the primary-payer reform. Why? More people insure privately and save more, so fewer ultimately rely on Medicaid. Since aggregate Medicaid outlays fall, the affluent see their tax bill decline!

Implications from our research

Population aging in the United States is driving increased demand for long term care services for the elderly. Nevertheless, few Americans purchase private LTCI insurance and instead must pay for expensive long-term care episodes out of pocket. Our research uses a quantitative structural model to consider reforms to the LTCI market. We show that the current “secondary payer” design of Medicaid discourages people from purchasing private LTC insurance. Making Medicaid the primary payer—while keeping the means-tests—would allow households to top off public coverage with private insurance. This simple shift would increase private coverage, enhance financial security, and reduce public spending.

The views expressed here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland or the Federal Reserve System. Nothing in the text should be construed as an endorsement of any organization or its products or services. No statements here should be treated as legal advice.